Path to a New Constitution in Chile: How the Unthinkable Became the Inescapable

Although public demand for a new constitution has long been present in Chilean political debates, it took weeks of sustained mass protests and a building sense of crisis to get parties from across the political spectrum to agree on a path to a new disposition. The Agreement is a critical first step, but, in a context of deep popular mistrust of the political class, the crafting of a legitimate constitution requires transparent and participatory processes and must avoid appearances of behind-the-scene self-dealing– write Professor Lisa Hilbink and Valentina Salas.

Introduction

Chile’s 1980 Constitution, inherited from Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship, has never had popular support. Although it has been reformed multiple times since the return to democracy, social movements and academics have repeatedly called for constitutional replacement, and surveys have consistently shown this demand to have majority popular approval. Not only does the 1980 charter lack legitimacy because of its authoritarian origins, but, in a highly unequal society, it continues to serve as a barrier to reforms that would strengthen the public sector and seek to more equitably distribute wealth and power. However, when former President Michelle Bachelet pursued a participatory constitution-making process from 2015-2017, it wound up in a political dead-end. With the return to power of Sebastián Piñera in 2018, constitutional replacement was no more ‘a priority in Chile’s public agenda’. Piñera made clear in diverse public statements, including his electoral manifesto, that his government would only support constitutional amendments, not a constitutional rewrite.

It was thus a stunning moment when, on Friday, 15 November 2019, with support from the Piñera administration, congressional representatives from nearly all Chile’s political parties, across the political spectrum, signed an agreement to hold a binding, national plebiscite to decide whether and how to write a new constitution. The Agreement also lays out a calendar and some basic ground rules for the (anticipated) constituent process. Its authors emphasized that the new constitution would be elaborated on a ‘blank page’, such that nothing in the existing constitution would bind the drafting body. In the days since, universities and civil society organizations have gone into high gear to design civic education modules to meet the demand for information relevant to the constituent process. What was unthinkable just a few weeks ago has thus become a reality: a cross-cutting political agreement has opened a path not only to a definitive end of control by the ‘dead hand’ of the authoritarian past, but also to Chile’s first ever democratically-crafted constitution. How did this happen?

A reluctant concession to persistent popular demand

The first and most obvious answer is ‘18-O’, the shorthand for the uprising that began on 18 October 2019. Without the pressure from below through sustained mass mobilization, and the disruption caused thereby, it is unlikely we would be writing this article. In an uprising driven by pent-up rage over inequality, exclusion, and perceived systemic injustice, citizens have insisted on constitutional replacement. The 1980 Constitution was designed to entrench a neoliberal socio-economic model by limiting the scope of majority decision making. As such, in order to clear the way for and constitutionalise more redistributive policies (which are at the heart of the popular demands), constitutional change is perceived as necessary.

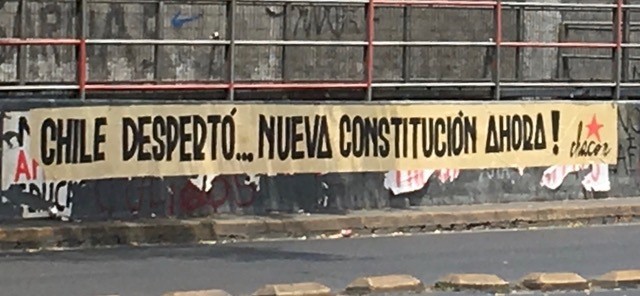

If and when a new, democratic constitution goes into effect in Chile, it will be a major triumph for the Chilean people. Not only did they ‘wake up’, but they gave a huge wake-up call to the elite, and demanded, in banners, posters, and graffiti, a ‘New Constitution Now!’ Surveys conducted since the start of the uprising have shown that upwards of 80% of respondents favor a new constitution. And the support is not just passive: organizations and individual citizens around the country have spontaneously convoked hundreds of town hall-type meetings (cabildos), focusing on different themes: e.g., inequality, environment, housing and land, gender issues, and, increasingly, constitutional change. In short, the mobilized citizenry has made the call for a new constitution, via a plebiscite and a constituent assembly, one of its central demands.

Piñera had initially rejected any proposal for a new constitution.

For several weeks after the start of the protests, however, the response of the Piñera government was a combination of repression, piecemeal reforms, and a decisive rejection of any proposal for a new constitution. To be sure, the government framed the crisis as one about public order and security. On 19 October, Piñera declared a ten-day state of emergency, which included military deployment into the streets and a curfew. He claimed that the government was ‘at war with a powerful enemy’. This angered the vast majority of law-abiding Chileans, leading, on Friday, 25 October, to the largest street mobilizations since the end of the Pinochet dictatorship (involving at least 1.2 million protesters in Santiago alone). Meanwhile, in terms of social reforms, the government offered up what many citizens viewed as paltry policy changes, such as a 20% increase in miserably low pensions, a rate freeze on electricity, and a still insufficient minimum monthly wage of around $435 ($350,000 Chilean pesos).

The executive’s intransigence began to erode after the cabinet shuffle on 29 October, which brought several younger and fresher faces into key offices, including the Ministry of the Interior.

To be sure, Piñera’s very first expression of openness to a new constitution was on 30 October, when, in reply to a question regarding a constitutional rewrite, he stated, ‘I do not dismiss any structural reform’. Over the next week, public order continued to deteriorate, with skirmishes between police and protesters producing human rights abuses (including scandalous rates of eye injuries), and looters and vandals setting fire to universities and historical buildings, as well as continuing to target businesses.

The National Association of Municipalities orchestrated a push from below to try to pressure the President to respond to the popular demand for a new constitution.

In this context of spiraling violence and a seemingly floundering government, on 7 November, two decisive events took place. First, Piñera met with the National Security Council (COSENA), a body created under the Pinochet dictatorship that advises the President on national security issues and is composed of the Commanders-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and the National Police (Carabineros), the Comptroller (Auditor) General, and the Presidents of the Chamber of Deputies, Senate and the Supreme Court. In the meeting report, the civilian authorities made clear to Piñera that the country did not face a national security crisis, questioning the appropriateness of the meeting. The Comptroller mentioned that COSENA meetings were a bad habit of an earlier era in which civilian power was subordinated to the military, and the President of the Senate declared his hope that exceptional measures, such as declaring a state of emergency, won’t be applied again in the future.

Piñera was gradually being forced into accepting a democratic way out of the crisis. On the same day, the National Association of Municipalities, which groups mayors and city council members of nearly all municipalities in Chile (330 out of 345), and is led by a politician from the President’s political party, voted to hold, at the municipal level, a non-binding ‘consultation’ (plebiscite) on 7 or 8 December 2019, in which people would be asked whether or not Chile needs a new constitution and about the main demands around the social crisis (following the Agreement towards a new constitution, the municipalities are going forward with a consultation on social policy priorities, to be held on 15 December). This collective initiative of municipal officials was remarkable in that it united mayors from across the country and across the political spectrum, representing rich and poor municipalities, in a push from below to try to pressure the President to respond to the popular demand for a new constitution. The decision was welcomed by social actors, fueling cabildos (town-hall type meetings) across the country.

Trade unions, the Association of Judges and several left-leaning opposition groups insisted on a new constitution as the only way out of the crisis.

But it was not until 10 November that the government took a clear stance on the constitutional debate. Gonzalo Blumel, the (41-year-old) new Minister of the Interior, made a televised announcement that the government would pursue a constitutional rewrite, but would do so via a ‘constituent Congress’, implying that it would be a process conducted by the sitting legislature.

This was anathema to the public, who had been demanding a ‘constituent assembly’ composed not of politicians, whom they perceive to be self-dealing, but of average citizens. It was also unsatisfactory for political parties in the opposition, or the municipal leaders who were moving ahead with their national consultation plan. It was, however, the first direct concession on the part of the government to the societal demand for a new constitution, and public discussion on constitutional change intensified. By Monday, 11 November, the current (1980) constitution, which is sold in bookstores and kiosks on city streets around the country, became the second best-selling book in Chile.

On Tuesday, 12 November, a variety of unions and social organizations (from education, transportation, mining, public sector, etc.) held a national general strike. A march in Santiago drew 80, 000 people, with large crowds in other major cities, as well. In this context of nation-wide mobilization, the National Association of Judges issued a statement in support of a new constitution, and fourteen opposition (Left and Center-Left) parties declared that ‘the only possibility to open a way out of the crisis is via a New Constitution’. The peaceful marches associated with the general strike were followed by the setting of fires and looting in several major cities in the country.

The Agreement towards a new constitution is perceived as having been made behind the scenes and possibly as a delaying strategy.

When Piñera emerged to speak to the nation that night, most people were expecting him to declare another state of exception. Instead, Piñera announced that his government would be moving forward with three pacts: for peace, for justice, and for a new constitution. Explaining the decision, five days later, Piñera remarked: ‘That night, Tuesday night, as President of Chile, I had to decide between two very difficult paths. The path of force, through the decree of a new constitutional state of exception, or the path of peace. Our national emblem says, “by reason or by force”. That night we chose the path of reason, in order to give peace a chance’. At this pivotal moment, then, when the crisis peaked, the President and his political allies decided that the political costs of repression were too high, and the option to open the path for a new constitution became inescapable.

Some are urging gender parity, reserved seats for indigenous representatives, a voting age of 16, and a mandatory vote in the constitution of an eventual constitution drafting body.

The next morning, the President of National Renovation (RN), Piñera’s political party, declared in an interview that a political agreement was needed immediately because the crisis was turning too critical: ‘This needs to happen today or tomorrow at the latest ... We need to give a sign to these men who are setting fires and looting as if we were in the wild west … a constitutional route that satisfies everyone’. Congressional representatives thus commenced intense negotiations. Two days later, they announced the Agreement, signed not only by legislators from the Center-Left and Left, who had supported Bachelet’s constitutional rewrite efforts, but also by all the parties in the rightwing governing coalition, including the hardline UDI (Unión Demócrata Independiente), whose founder, Jaime Guzmán, was the primary author of the 1980 Constitution. The Communist Party initially opted not to participate in the negotiations or sign the 15 November Agreement, but subsequently agreed to support the plebiscite and the constituent process. Elected officials from across the political spectrum have thus made a written commitment, whether sincere or strategic, deep or shallow, to a constituent process whose objective is ‘to reestablish peace and public order in Chile in total respect for human rights and the democratic institutions in place’.

Hopeful beginning, uncertain destination

For now, it seems the steps towards a new constitution have contributed to the relative calm. Of course, there are myriad issues still to be ironed out, and the process could still founder. As always, ‘the devil is in the details’, so it remains to be seen if the broad agreement about the path for a new constitution will persist through the discussion on specificities. Already, debates have emerged around how the two-thirds approval rule for all decisions of the constituent body will work in practice, and opposition parties are proposing additions to the Agreement regarding specific electoral rules for an eventual constituent convention. Beyond those that govern regular legislative elections (noted in the Agreement), they are urging gender parity, reserved seats for indigenous representatives, a voting age of 16, and a mandatory vote.

The political parties that signed the agreement appointed a Technical Commission which is already working to transform the agreement into constitutional reform bills and will propose further details for the constitutional process. The challenges are not only technical, however. The way that this Commission conducts its work and communicates with the public will be crucial, given the deep mistrust of the political class in society. Citizens and social organizations have already criticized the Agreement, which is perceived as having been made behind the scenes and possibly as a delaying strategy. Chile’s popular uprising, as much as a protest against distributive inequality and injustice, reflects a societal demand for respect, dignity and participation, a plea from citizens to be taken into account. It is thus crucial that political leaders design transparent mechanisms and find ways to give citizens voice in the decision-making process towards a new constitution.

Lisa Hilbink is Associate Professor and Valentina Salas is doctoral candidate at the Department of Political Science, University of Minnesota.

Comments

Post new comment