Reforming the Dutch Constitution to ensure ‘Future Readiness’ of its Democracy

The Netherlands is considering reforms related to the electoral system, the workings of the bicameral system and the constitutional amendment procedure in order to enhance both the representativeness of the Lower House and the corrective role of the Upper House. Whether the proposed reforms will pass procedural hurdles for constitutional amendment and effectively address the challenges Dutch democracy is facing remains to be seen. – writes Eva van Vugt.

In June 2019, the Dutch government announced that it is preparing legislative proposals aimed at strengthening parliamentary democracy. The announcement responds to an extensive report by a State Commission, an advisory body established in 2017 to assess the ‘future-readiness’ of the Dutch parliamentary system. In the report, the Commission identified problems for both democracy and the rule of law and proposed various solutions, some of which would require constitutional amendments. The government has indicated plans to adopt several of them. Most notably, it will propose changes to the electoral system of both Houses of Parliament. In addition, the government will prepare a proposal to modify the constitutional amendment procedure.

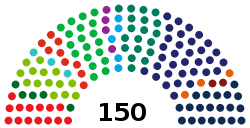

The Dutch Constitution is a sober document. It only comprises the most fundamental principles of government and leaves the rest up to the legislature. Parliament (Staten-Generaal) represents the entire people of the Netherlands, and consists of a Lower House (Tweede Kamer) and an Upper House (Eerste Kamer). The Lower House consists of 150 members, whereas the Upper House consists of 75 members. The elections for both Houses are conducted on the basis of proportional representation. Members of the Lower House are elected directly by Dutch nationals. Members of the Upper House are elected by provincial councils within three months of provincial elections. The government or the Lower House presents a legislative proposal, which requires a simple majority in both the Lower and the Upper House. The Lower House has the right to amend legislative proposals, while the Upper House may only veto such proposals.

Changing the electoral system for the Lower House

According to the State Commission, the system of proportional representation does fairly well in ensuring the representation of the diversity of political opinions in Dutch society. At the same time, the Commission claims that not everyone is substantially represented in the Lower House, therefore leading to the lack of parliamentary resonance with the political opinions of some citizens. Consequently, these citizens do not trust that Parliament adequately promotes their interests, which in turn can lead to alienation from the parliamentary system.

The Commission advises the government to revise the electoral system. In the current electoral system, every voter has to vote for a specific person on an electoral list. Political parties compile these lists before parliamentary elections, and the candidate heading the electoral list is usually the party’s political leader. The Commission suggests the granting of two options to voters: they either vote for a specific candidate on an electoral list (preferential vote) or vote for the electoral list as a whole. The idea is that preferential votes will carry considerably more weight in the new system than they do now, which would in turn enhance the representativeness of Parliament.

The reasoning behind the suggestion is as follows. Many voters in the Netherlands have no specific preference for one candidate over the other. Instead, they support a political party. The current electoral system nevertheless forces them to cast a preferential vote. Voters therefore generally vote for the number 1 on the list: the party’s political leader. The party leader, however, does not necessarily rely on preferential votes for obtaining a parliamentary seat. Since the party leader heads the list of a political party, his or her seat is secured as soon as the political party obtains sufficient votes to reach the electoral threshold.

The proposed reforms to the manner of election of members of the lower house could strengthen the regional representation of citizens

When the party leader obtains a large number of preferential votes, the preferential votes on other candidates have less impact on the composition of the Lower House. By enabling voters that have no special preference for a candidate to vote for an electoral list as a whole, preferential votes will carry more weight than under the present system. The Commission believes that this will contribute positively to the representativeness of Parliament, and consequently reinforce the trust of voters in the parliamentary system, because it will be easier for their preferred candidate to obtain a seat in Parliament. Not only should this strengthen voters’ feeling that their vote actually matters, but it should also foster the representation of as many political opinions in Parliament as possible.

The government has endorsed the suggestion of the Commission and believes that under the new system voters will identify themselves more easily with their representatives. It also expects that the new system will strengthen the regional representation of citizens. Citizens living in the more rural parts of the Netherlands tend to feel inadequately represented by MPs, since the majority of MPs are from the Randstad (the urban region that comprises the cities of Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam and Utrecht). If these citizens can cast a preferential vote on a candidate who is from their own region, they will be more confident that their local interests are represented too.

Changing the electoral system for the Upper House

The government also aims at strengthening the position of the Upper House. As mentioned before, the Upper House is elected indirectly through provincial councils, not directly by the people. For this reason, the political primacy in the Dutch system lies with the Lower House. The Upper House is expected to guard the quality of legislation and not to develop public policy. This explains why its powers are rather limited, with no right of initiative or amendment.

The authority of the Upper House is not a given. Each time the Upper House rejects a legislative proposal, it can count on harsh criticism from various sides. Those who regard the Upper House as a chambre de reflection argue that the Upper House is too ‘politicized’, in the sense that it rejects legislative proposals based on party-political considerations instead of ‘neutral’ objections. On the other hand, those who acknowledge the political character of the Upper House argue that political primacy should lie with the Lower House. In their view, the Upper House lacks the democratic legitimacy to reject legislative proposals. By implication, the Upper House should better be abolished.

In the absence of a constitutional court, the Upper House is the last resort to ensure the propriety and constitutionality of legislation.

Against this background many looked expectantly at the Commission: would it advise the abolition of the Upper House or not? The Commission was, however, very outspoken: as the guardian of the quality of legislation and as a bulwark against the potential menace of democracy, the Upper House has a vital role to play in the Dutch system of checks and balances. While in many other countries a constitutional court guarantees the constitutionality of legislation, the Dutch Constitution prohibits constitutional review by the judiciary. As a result, the Upper House is the last resort to ensure the constitutionality of legislation. The abolition of the Upper House would hence erode the – already meager – system of checks and balances. The Commission therefore believes that the position of the Upper House needs to be strengthened for it to fulfill a meaningful corrective role in the Dutch constitutional system.

The government agrees with the Commission that the position of the Upper House should be enhanced: not by strengthening its democratic mandate, but rather by further disconnecting it from the political mood of the day. For that purpose, the government wants to change the way in which the members of the Upper House are elected. Members of both Houses are currently elected for four years, but the elections do not take place on the same date. The elections for the Lower House occur on a date different from the elections for the provincial councils, and only after the members of the provincial councils are appointed will they choose the members of the Upper House.

The government has proposed a longer term for members of the Upper House, with staggered elections.

After Lower House elections, constitutional convention dictates that a government is formed of parties that together have a majority of seats in the Lower House. For a long time it was common for a government to have a majority in both Houses. That has become more difficult due to increasing political fragmentation. In 2010 and 2012, for example, the coalition parties could only count on a majority of the seats in the Lower House, not in the Upper House. The current government moreover lost its slim majority in the Upper House after the elections for the provincial councils in March 2019.

Against this background the government expects that inter-house friction will arise more often within parliament – especially when the Upper House rejects a legislative proposal initiated by the government and supported by a majority in the Lower House. The government therefore wants to propose a longer term with staggered elections: members of the Upper House would be elected for six years instead of four, and half of the seats would be contested every three years. As a result, changes in the party-political landscape will only have an indirect and delayed effect on the composition of the Upper House. This could enable the Upper House to rise above party-political squabble. The government moreover hopes that the elections for the provincial councils will then be about actual provincial matters instead of being captured by opposition parties campaigning against the central government (the provincial elections in March revolved around the hashtag #stemzeweg, i.e. #votethemdown).

Changing the constitutional amendment procedure

Besides changing the electoral system for both Houses of Parliament, the government has also endorsed the recommendation of the Commission to change the procedure for amending the Constitution. The constitutional amendment procedure that is currently in place is quite rigid: it consists of two readings, intervening elections, and requires a two-thirds super-majority in both Houses in the second reading. The double supermajority requirement allows 26 out of 75 senators to block a constitutional amendment even if 100 or more of the 150 directly elected members of the Lower House have supported the amendment.

As the Commission, the government feels that the tension between the veto power of the Upper House and the political primacy of the Lower House during the final stage of a constitutional amendment procedure negatively affects the position of the Upper House. For this reason, the government wants to change the second reading of the constitutional amendment procedure. Instead of having both Houses considering the constitutional amendment separately, they would sit in a joint session in order to consider the constitutional amendment. The constitutional amendment would still require a qualified, two-thirds majority, but in a joint session, meaning that at least 150 out of the total 225 members of Parliament have to vote for the constitutional amendment. As a result, 26 senators would no longer have the power to block a constitutional amendment on their own.

Conclusion

While the intention behind the proposed reforms is clear, there are questions on whether the proposed reforms can achieve the stated goals. The proposals also face practical challenges of garnering the needed political consensus for their implementation. Notably, extending the parliamentary terms for the Upper House and changing the constitutional amendment procedure require a formal constitutional amendment, and the threshold for constitutional amendment is high.

The proposed changes regarding the election method for the Upper House may lack broad support. Moreover, instead of further depoliticizing the Upper House, there might as well be calls for either abolishing the Upper House or strengthening its democratic mandate. Whether the members of the Upper House in turn will consent to a less decisive power in the constitutional amendment procedure is also critical. Meeting in a joint session in the second reading of such a procedure might reduce the tension between the Lower and Upper House. The proposal moreover does not render the constitutional amendment procedure too flexible: the two readings, intervening elections, and a qualified majority in second reading will remain in place and serve as important safeguards against hasty decisions.

The reform of the electoral system for the Lower House will only require an ordinary legislative amendment and hence a simple majority. This significantly increases the chances of success compared to the other two envisaged changes. The more fundamental question, however, is whether changing the electoral system will increase the representativity of and trust in the Lower House. Even if the Commission were right in its problem analysis (i.e. that there is a problem of substantive representation in the Netherlands), the question is whether a change in the design of the system will address this problem. The solution might as well just lie with the behavior of Dutch MPs and political parties.

The proposals show that even mature and stable democracies such as the Netherlands need to consider updates to their constitutional system occasionally. A system may work fine in quiet times, but everything liquefies under pressure. Crucially, in typical Dutch mentality, the government believes that prevention is better than cure. The future will tell us whether Parliament agrees.

Eva van Vugt is a Ph.D. researcher in constitutional law at Tilburg University.

Comments

Post new comment