Two Drafts, Three Referendums, and Four Lessons for Constitution-making from Chile

♦ ♦ ♦ This article is part of a series where experts provide insights into Chile's constitution-making process. Read more. ♦ ♦ ♦

Constitutional fatigue, lack of political consensus, and a broader rejection of the political elite may have contributed to the failure of Chile’s draft constitution at referendum. But the experience also offers four key considerations for future constitution-making processes around the world: the significance of context over text, the necessity of political guardrails in the drafting process, the challenges of writing constitutions in the era of social media and political polarization, and the diminishing symbolic value of new constitutions for effecting real change – writes Sebastian Soto

Chile did it again. For the second time in just over a year, a draft of a new constitution has been rejected in a referendum. While the first rejection placed Chile among the few instances in which draft constitutions were not approved, the latest outcome result transforms us into a unique case.

On 17 December 2023, nearly 12.4 million people voted, constituting 85 per cent of the electoral roll, with mandatory voting. Of these, 55.8 percent rejected the new text, while 44.2 per cent approved it. The result was narrower than that of the first referendum, but equally categorical.

Why was the draft rejected?

Why was the text rejected even though the new process tried to deal with all the mistakes of the previous one? If the problem of the first process was that it was disconnected from traditional political parties (or was even in conflict with them), this process included the political parties from the start. If the main errors of the first process were the procedures and rules to write the new constitution, this time the procedures had several institutional safeguards that would prevent overreach (e.g., an Expert Commission to draft the initial text, twelve guiding principles). If one of the problems of the first text was that it included some exuberant clauses, this text had fewer rights, fewer principles, and fewer hyper-specific rules. Still, the text was again rejected.

Here I present three reasons to better understand this defeat.

The first reason lies in constitutional fatigue. After a decade of constitutional discussions, the abstract idea of a new constitution no longer elicits the same enthusiasm. Surveys indicate that people recognize it will not automatically transform their lives and that many of the promises associated with a new constitution will not come to fruition. The rejection may then reflect society “slamming the door” on abstract ideas, seeking in turn more tangible changes.

In just over a year, Chileans were once again offered a text that was not the product of political consensus . . .

The second reason is that, in just over a year, Chileans were once again offered a text that was not the product of political consensus. This time, the right advocated for an approval vote, while the left called for rejection; in the first process it was the other way around. Inexplicably, the Partido Republicano (Republican Party), which obtained 22 of the 50 seats in the elected Constitutional Council, did not pay enough attention to polls indicating the public’s desire for political agreements. The Republican Party, positioned at the far right of the Chilean political spectrum, pursued a different path and decided to exacerbate polarization through pushing specific divisive amendments and rhetoric. Initially this strategy was resisted by the center-right parties, but was eventually accepted. For the left, capitalizing on polarization provided an opportunity to gradually break away from an uncomfortable draft.

A consensus text was at one point, however, possible: the appointed Expert Commission, with half of its membership nominated by left-leaning political parties and half by right-wing political parties, including the author as a member, successfully crafted a text agreed to by all representatives, from the Republican Party to the Communist Party. This text was subsequently submitted to the Constitutional Council for finalization. Unfortunately, this draft was discarded by the Council early in the process.

The third explanation is that, in recent years in Chile, the “No” vote has always won. Initially, people voted for a new constitution rejecting the current one. Subsequently, they voted “no” to the first draft and, on 17 December, they voted against the second draft. Furthermore, the outstanding result of the Partido Republicano in the elections for the Council could be read as a rejection of the entire process, as this party was one of the few voices against this second constitution-making process. In other words, the vote can be interpreted as a rejection of the political elite and the political system. Yesterday, Chilean voters rejected a left-wing constitution; today, a right-wing one. So, what lies ahead?

This trend is dangerous because it opens the door to populism, which has taken root in both left- and right-wing political parties in Chile. The two constitutional processes arose from broad-based political agreements (including the “Agreement for Social Peace and a New Constitution” in November 2019 and the “Agreement for Chile” in December 2022), but have culminated in confrontation. Instead of seeking unifying opportunities, the referendums seem to have widened the distance between the people and politics.

The political elite must soon seek a means to reduce polarization and deliver political signals to prevent the arrival of populism. Playing the constitutional card was not effective in achieving this; in fact, it may have even exacerbated the problem.

What comes next?

Both referendums have ended up reaffirming the current Constitution: drafted under Pinochet, amended on countless occasions, and today endorsed, after significant constitutional reforms in 2005, by former President Lagos. The old order, which seemed to be collapsing after the 2019 “social outburst”, now has a new opportunity. But it is not possible to anticipate how long this resurgence will last. The government and all major political parties have pledged not to call for a third constituent process because of the widespread discontent, and it is likely that we will not hear talk of a new constitution for many years.

Nevertheless, the current Constitution does require changes, some of them significant, particularly in areas like the political system, judiciary, and catalog of rights, among other issues. If politics were a space of pure rationality, specific amendments would soon be approved in Congress. However, with two electoral years ahead, during which passions and interests may cloud rationality, the pivotal question arises: will there be political leaders willing to address these issues and, in the process, pay the associated political costs?

What, if anything, can be learned from the Chilean constitution-making experiences?

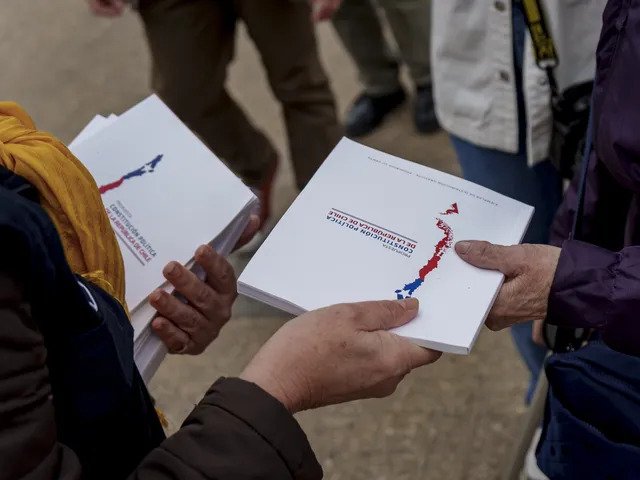

Chile has been a constitutional laboratory over the past four years. There have been two constitutional drafts, two (mandatory) referendums, an initial referendum to determine whether to change the current constitution and to determine the mechanism for doing so, the establishment of two different constituent assemblies with their own rules and procedures, multiple processes for citizen participation, and more.

This real blend of experiences offers an opportunity to pose at least four crucial questions that should be contemplated by future constitution-making processes around the world.

One: Text or context?

Constitution-making processes focus on the text itself: a catalog of rights, constitutional principles, and institutional arrangements. These texts must also incorporate specific clauses that resonate with people’s interests and demands, necessitating a degree of public participation.

However, Chile’s experiences underscore the importance of context, which might be as critical (if not more so) than the actual text. People cannot fully anticipate the scope and implications of proposed constitutional provisions and, in the end, decide how to vote based on contextual factors: the political moment, their perception of the process, and the opinions of social and political leaders.

In light of this, constitution-making processes should be studied as moments to reevaluate broader societal contexts and not only as opportunities and mechanisms to write new texts.

Two: Where is the containment?

The eternal temptation of constituent powers is the dream of unlimited power. This temptation has enjoyed theoretical support for centuries. The Chilean processes employed several mechanisms to control that temptation: judicial review of procedural rules by the Supreme Court; high voting thresholds to approve each article of the new constitution at the drafting stage (two-thirds in the first process and three-fifths in the second), a set of 12 fundamental principles that had to be respected, and more. These constraints were all imposed by law.

These mechanisms, however, were not enough. Such processes also need political containment agreements or practices, whether formalized or informal, in order to facilitate collaborative drafting (sharing both the “pencil” and the “eraser”) when writing the clauses of the new constitution. While legal rules for containment are important, political containment practices are essential. We should pay more attention to the latter.

Three: Mechanisms to escape a crisis or to delve deeper?

Traditionally, constitution-building has been seen as one possible vehicle to escape political crises. In October 2019, Chile followed that path after the so-called “social outburst”. Yet, the last four years have demonstrated that writing new constitutions in contemporary times presents new difficulties that can lead to even worse scenarios for the elite and the political health of a country.

The full transparency and absence of mediation in social media are incompatible with complex deliberative processes.

One of these new challenges arises from writing constitutions in the era of digital social networks. Although social media makes it easier to connect with people, these platforms increase the costs of reaching political agreements and compromises. The full transparency and absence of mediation in social media are incompatible with complex deliberative processes. The author’s personal experience in the Expert Commission showed that it was only possible to compromise and agree on a common text because many of the negotiation spaces were private. Is it possible to maintain a certain degree of opacity needed for political negotiation without fostering distrust in the process?

The second challenge revolves around confronting populism and polarization. As suggested repeatedly by the Venice Commission, ‘the adoption of a new and good constitution should be based on the widest consensus possible within society’. But how could this be possible in times of deep polarization? Although there are some experiences of writing new constitutions in highly divided societies, it may be prudent to question whether constitution-making will exacerbate rather than heal rifts. Populist leaders could exploit the new text to increase polarization through constitutional populism, and open new space for the divisive rhetoric of “friends” and “enemies”.

Four: A hollow symbol?

New constitutions, especially in Latin America, are full of symbolism: a new beginning, a wonderful future, and numerous state commitments. They could be called “Aladdin’s constitution”: the one that makes all your dreams come true.

The Latin American experience of recent decades shows that this symbolic value is being lost. New constitutions within the region have not improved living conditions but have served the interests of autocrats. In Chile, the first constitutional process possessed some symbolic value, but it rapidly lost popular support in the first months. The second process never had an opportunity to increase its levels of popularity. It seems that, sensibly, citizens have perceived that new constitutions do not necessarily change lives, but they can make them worse.

The loss of the symbolic value of new constitutions should be embraced to discourage politicians from investing so much political muscle in this direction. It is time to pay more attention to specific policies that genuinely improve people's lives.

Sebastián Soto is an Associate Professor of Constitutional Law at Universidad Católica de Chile. He was vice-president of the Expert Commission in the 2023 constitution-making process.

♦ ♦ ♦

Suggested citation: Sebastián Soto, ‘Two Drafts, Three Referendums, and Four Lessons for Constitution-making from Chile’, ConstitutionNet, International IDEA, 22 December 2023, https://constitutionnet.org/news/voices/two-drafts-three-referendums-and-four-lessons-constitution-making-chile

Click here for updates on constitutional developments in Chile.

Comments

Post new comment