Introduction

Since independence, Myanmar has had three constitutions: the Constitution of 1947, the Constitution of 1974 and the Constitution of 2008. The country also experienced long periods of non-constitutional rule where military governments ruled without a clear constitutional basis (1962-1974, 1988-2011 and 2021 onwards).

Myanmar gained independence from the British Empire in 1948. Initially, under its 1947 Constitution, the country had a democratic system and a form of asymmetric federalism. However, following a coup in 1962, a military government was established and ruled without a constitution for 12 years. In 1974, the military institutionalized its rule by adopting a new constitution that transformed the regime from a military dictatorship to a consolidated one-party dictatorship. In 1988, anti-government protests calling for democracy led to the collapse of the one-party regime. A new military command – the State Law and Order Restoration Council – took over, suspended the 1974 Constitution and ruled the country without a constitution until 2011 when a quasi-civilian government took power. During that period, the military regime suppressed almost all dissent and was accused of violating human rights, resulting in international isolation and sanctions.

A military-drafted constitution was adopted in 2008 following a referendum that was criticized as deeply flawed. The 2008 Constitution, which came into force in 2011, enshrined the military’s vision of so-called ‘disciplined democracy’, and was part of its strategy for a gradual and partial withdrawal from politics and governance while retaining power in the background. It provided for a power-sharing arrangement between civilian authorities and the military whereby the military retained substantial influence over key aspects of policy and a veto power over constitutional amendments. It enabled the formation of two successive quasi-civilian governments, led respectively by President Thein Sein (2011-2015) and de facto by State Counsellor Aung Sang Suu Kyi (2016-2020) following the victory of the National League for Democracy (NLD) in the 2015 general elections. Aung Sang Suu Kyi had been constitutionally barred from holding the presidency, but the NLD found a loophole that effectively allowed her to lead the civilian part of the government as state counsellor, an office not foreseen in the 2008 Constitution (but also not banned). A peace process with Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs) that had been fighting against the Burmese military for decades was initiated and economic and political introduced as part of a gradual transition to a more democratic framework, albeit under the stewardship of the military. A series of attempts to amend the 2008 Constitution to make it more genuinely democratic and federal failed, however.

On 1 February 2021, the Myanmar military staged a coup and unconstitutionally declared a national state of emergency, transferring all state powers to the commander-in-chief. The pretext for the coup was unproven allegations of electoral fraud in the 8 November 2020 general elections, which saw the governing NLD winning 79.5 per cent of the elected seats in the Union parliament, and most seats in the state and region assemblies.

The general public and civil servants quickly mobilized against the military coup through a nationwide protest movement known as “the Spring Revolution”. A group of MPs who won seats in the 2020 general elections – and with the endorsement of 80 per cent of all elected MPs – formed the Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH) to represent the legitimate legislature, released a Federal Democracy Charter (FDC) detailing the terms of an inclusive alliance against the military, and together with EAOs, the popular protest movement and civil society, established the National Unity Government (NUG) as an interim executive branch tasked with defeating the military junta. This broad coalition of pro-democracy forces also committed to developing a new federal democratic constitution for the country, while declaring the 2008 Constitution obsolete.

The 1935 Burma Act

The Burma Act of 1935, an act of the British parliament, separated Burma, as it was then known, from British India. This act established a dyarchical (dual rule) system, where the British Governor had exclusive control of foreign affairs, defence, security and the ‘Frontier Areas’, while self-governing institutions – in the form of a partially elected bicameral parliament and a cabinet – had limited authority over some internal affairs. The British Governor had vast reserve powers, and was therefore able to intervene in the political system, in principle to promote 'peace, order and good government', but also to protect British economic and strategic interests.

The Burma Act of 1935 made a distinction between so-called Ministerial Burma (the Bamar-majority areas, broadly equivalent to the current regions, previously known as divisions) and the ‘Frontier Areas’ (the ethnic-minority dominated areas, broadly equivalent to the current states, except Rakhine). While the Frontier Areas were largely outside the direct control of the Burmese Cabinet and subject to the direct supervision of the Governor, this supervision was mostly exercised in a hands-off manner, and local elites applied customary law.

1974 Constitution

During WWII, British Burma was occupied by Imperial Japan, which installed a nominally independent puppet government, and became the scene of intense fighting: the Bamar-dominated centre fought on Japan’s side and the ethnic minority areas in the borderlands were on the side of the Allies. In 1945, after the Burma independence movement switched allegiances from Japan to the Allies, Burma came back under British control.

Myanmar’s first Constitution as an independent country was written in 1947 when the British government and the interim government of General Aung Sung reached an agreement on full independence from Britain.

In January 1947, the interim government of General Aung San and the British government reached an agreement on full independence from Britain. This agreement, known as the Aung San-Attlee agreement, also provided that the unification of the Ministerial Burma and the Frontier Areas into a single independent country could only occur with ‘the consent of the inhabitants of those areas’. Two weeks after the signing of the agreement with Britain, Aung San signed an agreement at the Panglong Conference, with leaders representing the Shan, Kachin, and Chin ethnic groups. In this agreement, these leaders agreed to join a united independent Burma, under the conditions that they would have ‘full autonomy in internal administration’and that ‘citizens of the frontier areas shall enjoy rights and privileges which are regarded as fundamental in democratic societies’.

Aung San’s political party, the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League (AFPFL), prepared a preliminary draft constitution that was then submitted to a partially elected Constituent Assembly. The Constituent Assembly worked from June to September 1947. However, the constitutional negotiations were disrupted by the assassination of Aung San and other cabinet members in July 1947. The Constituent Assembly made substantive amendments to the initial draft constitution after Aung San’s death and adopted the Constitution on 24 September 1947. The 1947 Constitution was the first Constitution of an independent Union of Burma.

The 1947 Constitution established a parliamentary system. There was a ceremonial president who acted as constitutional head of state, while effective executive power was exercised by a prime minister and cabinet, which were chosen by and from – and were politically responsible to – the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of the bicameral parliament. The Constitution also provided for an asymmetric federal structure that gave different degrees of autonomy to different states. This federal system had some unusual features:

- Federalism was not applied to the whole country: the Bamar majority areas, carved essentially from the old Ministerial Burma, in effect existed under a unitary state, and the Union Parliament legislated for them directly.

- Those areas that did have special autonomy did not have it on equal terms. Shan State, Kachin State and Karenni State (which became Kayah State in 1952) had the full range of state powers. Prior to becoming Karen State in 1951, the Kaw-Thu-Lay region had a lesser degree of autonomy as a ‘Special Region’. The Chin had no state of their own but did have more limited administrative autonomy as a ‘Special Division’.

- Certain states – Shan and Karenni – had a right to secession after ten years.

However, this arrangement was not accepted by all stakeholders. Some ethnic groups considered that this federal arrangement did not fulfil the commitment for full autonomy in internal administration for the Frontier Areas agreed upon in the Panglong Agreement. In 1961, ethnic leaders held a series of conferences on federalism and submitted constitutional amendment proposals to parliament to provide greater autonomy to the states. Notably, proposals included rearranging the division of legislative powers between the Union level of government and the states, and restructuring the upper house of Union parliament so that each state would have equal (rather than proportional) representation. These discussions were put to a halt in March 1962, when the military under General Ne Win staged a coup, partly in reaction to concerns over aspirations for greater autonomy.

Following the March 1962 coup, General Ne Win established a Revolutionary Council, made up of military leaders who ruled by decree with no constitutional basis until 1974. Basic freedoms were severely restricted and political parties were outlawed. In September 1971, General Ne Win appointed a 97-member Constitution Drafting Commission tasked with preparing a new constitution, under the close supervision of the Revolutionary Council. The Revolutionary Council conducted a referendum in December 1973 to endorse the new constitution, approved by over 90 per cent of the voters in a process whose fairness was questioned by many in the country.

The 1974 Constitution can be seen as an attempt to institutionalize military rule by transforming the regime from a military dictatorship to a consolidated one-party dictatorship. The resulting constitution was the opposite, in just about every respect, from its 1947 predecessor: the 1947 Constitution was bicameral, the 1974 unicameral; 1947 was a multiparty democracy, 1974 a one-party state; 1947 was an attempt to apply Westminster parliamentarism to a Myanmar context, 1974 was an adaptation of the Soviet-/Yugoslav-style constitution prevalent across the communist bloc in the Cold War era. Consequently, the Burma Socialist Programme Party became the only legally recognized political party dominating all the three branches of government.

The 1974 Constitution established a new territorial organization made up of seven states and seven divisions, and introduced the concept of formal equality between states and divisions. The seven divisions roughly covered the territories of what the British called Ministerial Burma (the Bamar-majority areas) and the seven states were broadly equivalent to the so-called Frontier Areas (the ethnic-majority areas). The states and divisions had limited power, as all legislative powers were exercised by the unicameral legislature at the central level. The judiciary was also subordinate to the party and no independent institutions were permitted.

The 2008 Constitution

In 1988, anti-government protests calling for democracy led to the collapse of the one-party regime. A new military command – the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), which later became the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) – took over, suspended the 1974 Constitution, and promised to hold democratic, multi-party elections. In June 1989, the military government officially changed the English name of the country from Burma to Myanmar.

Elections in 1990 gave Aung Sang Suu Kyi’s opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) 392 out of 485 parliamentary seats (80 per cent), while the military-backed party, the National Unity Party (NUP), won just 10 seats. However, the junta invalidated the results and placed the NLD leader under house arrest. In April 1992, the SLORC announced the formation of a National Convention tasked with preparing a new constitution. The constitution-making process and the design of the constitution was managed by the military junta. More than 85 per cent of the members of the National Convention were appointed directly by the SLORC, and only drafts prepared by the military were presented to the National Convention for deliberation. The NLD and other parties boycotted the process. The Constitution was eventually adopted in May 2008 in a referendum held just a few days after Cyclone Nargis. The results announced by the regime showed an overwhelming majority vote for the Constitution but there were numerous reports that the ballot papers were marked by state officials, regardless of the preferences of the voters. The 2008 Constitution came into force after the systematically rigged elections of 2010 and the formation of the new parliament and president-led government in March 2011.

Structure of Government under the 2008 Constitution

The 2008 Constitution enshrined the military’s vision of ‘disciplined democracy’. It provided for a power-sharing arrangement between civilian authorities and the military whereby the military retained substantial influence over key aspects of policy and a veto power over constitutional amendments. The 2008 Constitution established a centralised ‘Union System’ as state structure, and an assembly-independent system of government (where the head of the executive is elected by parliament but not responsible to parliament).

State structure

The 2008 Constitution established a 'Union system’ consisting of a Union level of government, and seven regions, seven states, six self-administered areas and one Union territory (the capital Naypyitaw). The bulk of legislative power and residual powers were granted to the Union level of government. The States and Regions were given limited legislative and executive powers but had their own partially elected assemblies. The Chief Ministers of State and Regions were appointed by the Union level executive. The centralized state structure was a contentious issue and a key reason for ethnic armed organizations’ continued engagement in armed conflict.

Executive branch

All executive power was vested in a president who acted as head of state and head of the executive (Art. 16, 57 and 199(a)). The president and the two vice-presidents were elected by an electoral college consisting of all members of the bicameral Union parliament (Art. 60). The system for choosing the president and the two vice-presidents ensured that one of those offices was always held by the military. The president and the vice-presidents could only be removed by impeachment proceedings requiring a two-thirds majority vote of all members of one of the two chambers of parliament (Art. 71). The president was not accountable to parliament, and therefore could not be removed without cause.

The president had a five-year mandate, renewable once (Art. 61). The president determined the size and structure of the cabinet and appointed and dismissed ministers at will (Art. 202). But the president had to assign responsibilities for finance and budgetary processes to the two vice-presidents, one for the Union and the other for states and regions (Art. 230). The president had extensive appointment powers and chaired several important bodies. Two were of particular importance: the National Defense and Security Council and the Financial Commission for recommendations on the budgets of the union and states/regions.

The Constitution separated the roles of president and Commander-in-Chief, with the latter being a senior general exercising substantial autonomy in relation to the government. Also, appointments to three key ‘power ministries’ (i.e., defence, home and border affairs) had to be made by the Commander-in-Chief, essentially placing these ministries under the direct control of the military (Art. 232(b)). Importantly, this included (until 2018) the General Administration Department, the backbone of state administration down to the local level.

Of note, Article 59 prohibited anyone with foreign nationality or relatives from running for president. This effectively excluded opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, whose children and deceased husband are British citizens. After the 2015 general elections, the newly governing NLD created, through legislation, a new position of State Counselor specific to Aung San Suu Kyi. The State Counselor was the de facto head of government, and the President became like a ceremonial head of state.

Legislative branch

There were legislative structures for the Union, States and Regions, and Self-Administered Zones or Divisions. Members elected into each of these legislative structures all had a five-year mandate. The bulk of legislative power (and residual powers) were granted to the Union-level legislature. States and Regions were given limited legislative responsibilities, but these notably included municipal affairs and thus allowed for variations in the management of local government. Ethnic Affairs ministers were directly elected in states/regions with significant minority populations, and were members of the legislature and cabinet of their respective state/region.

The Union legislature, known as the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, was bicameral. One chamber represented the people and townships and was called the Pyithu Hluttaw and the other represented the states and regions and was called the Amyotha Hluttaw. Both chambers were elected at the same time for a five-year term. Disagreements over bills between the two chambers were resolved through a simple majority vote in a joint sitting.

In the Union legislature, 25 per cent of seats in both chambers, as well as 25 per cent of seats in state and regional legislatures, were reserved for the military and appointed by the Commander-in-Chief. This gave the military veto power over constitutional amendments, which required a supermajority vote of more than 75 per cent of all members of the Union legislature (Art. 436), and enabled the military to dictate the pace and direction of any subsequent constitutional change.

Judicial branch

The 2008 Constitution established a single court hierarchy system. In this set-up, there was no division of the judicial power between the different levels of government. There was only one unified judicial hierarchy, controlled at the Union level. The judiciary consisted of the ordinary courts, the courts martial and the Constitutional Tribunal.

At the apex of the ordinary courts was the Supreme Court (which was the only ordinary court at the Union level). There was also one High Court in each State and Region, as well as District and Township courts. There was no judicial service commission to appoint or dismiss judges.

The Constitutional Tribunal was established to interpret the provisions under the Constitution, to vet whether the laws promulgated by the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, the Region Hluttaw, the State Hluttaw or the Self-Administered Division Leading Body were in conformity with it and to decide on Constitutional disputes (Art. 322). The Constitution provided that resolutions of the Constitutional Tribunal were final and conclusive (Art. 324). However, in 2012, parliament passed an (evidently unconstitutional) amendment to the Constitutional Tribunal law which downgraded the Tribunal’s authority from binding and final to declaratory and subject to review by the legislature, and initiated impeachment proceedings against the Tribunal’s members. In protest, all nine members of the Tribunal resigned.

The Armed Forces

The 2008 Constitution granted the military a central role in Myanmar politics. The 2008 Constitution effectively provided a separate regime for it with special privileges, immunities and representation in state institutions, such as the legislature and the cabinet, as outlined above. Also, unlike in many countries where the head of the executive is normally the commander-in-chief of the armed forces in line with the principle of civilian control of the army, the President in Myanmar was not the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. This position was retained by the military who effectively displaced the President in times of national emergency threatening national unity. Further, the National Defense and Security Council, dominated by the military, exercised important policy and executive functions.

Constitutional developments after the 2008 Constitution

After the passage of the 2008 Constitution, there were significant reforms in the economic and political spheres, including the release of Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest and allowing the NLD to compete in the 2012 by-elections, where it won 43 out of 44 parliamentary seats contested.Two successive quasi-civilian governments were formed under the 2008 Constitution, led respectively by former general President Thein Sein (2011-2015) and de facto State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi (2016-2020) following the victory of the NLD in the 2015 general elections. During that period, there were two main attempts to amend the 2008 Constitution through the formal amendment procedure. The first attempt took place from July 2013 to June 2015. On 25 July 2013, the lower house of parliament approved the formation of a committee to review the 2008 Constitution. The Committee submitted its report to Parliament on 31 January 2014, following which the parliament formed an ‘Implementation Committee’ that prepared two constitutional amendment bills before the 2015 elections. Among the proposed amendments, one aimed to remove the restriction that prevented Aung San Suu Kyi from serving as president. Another proposal consisted in lowering the threshold for amending the Constitution from 75 per cent to 70 per cent of all members of parliament. However, only one minor amendment with regards to qualifications for candidates to the presidency was approved.

In January 2019, the NLD initiated another constitutional amendment process in parliament that resulted in two amendment bills that concentrated primarily on reducing the role of the military in politics. Notably, these two amendment bills purported to gradually reduce the proportion of military appointees in parliament over the next three general elections, from a maximum of 25 per cent to 5 per cent in 2030. They also proposed altering the existing constitutional amendment procedure by reducing the approval threshold from 75 per cent to two-thirds of members of the Union Parliament. The amendment proposals also aimed to further assert civilian control by proposing the maintenance of civilian governance during states of emergency, and civilian decision-making over the appointment of all ministers. The two amendment bills were submitted to the Union Parliament on 27 January 2020. The vast majority of the 114 proposed amendments eventually failed to meet the 75 per cent threshold of parliamentarians. Only four minor amendments were approved, none of which significantly changed the Constitution.

Simultaneously, the government was engaged in a series of peace negotiations with some ethnic armed groups. These negotiations, however, never affected the constitutional framework for federalism, despite that being a key demand for peace by the ethnic minority groups.

The 2021 military coup and post-coup developments

On 1 February 2021, the Myanmar military detained high-level government officials, including President Win Myint and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, blocked newly elected parliamentarians from taking their seats and declared military-nominated Vice President Myint Swe as acting president. Myint Swe then, in violation of constitutional criteria and procedures, declared a national state of emergency transferring legislative, executive and judicial powers to the Commander-in-Chief, General Min Aung Hlaing. The military also announced that elections would be held at the end of the state of emergency, which could span one-to-two years according to the 2008 Constitution.

The pretext for the coup was unproven allegations of electoral fraud in the 8 November 2020 general elections, which saw the governing National League for Democracy winning 79.5 per cent of the elected seats in the Union Parliament. The military and its proxy party – the Union Solidarity and Development Party – claimed to have identified large-scale electoral fraud based on irregularities in the voter lists, but never provided concrete evidence.

In response to the coup, the general public quickly mobilized against the military’s attempt to take control over state power through a nationwide protest movement known as “the Spring Revolution” and a coalition of pro-democracy forces established a National Unity Government (NUG) to defeat the military junta. Civil servants en masse refused to take orders from the illegal coup-makers and formed a Civil Disobedience Movement comprising of up to 400,000 public sector workers. The international community has for the most part condemned the coup but has been hesitant to engage with either the military regime or the NUG.

Structure of the military regime

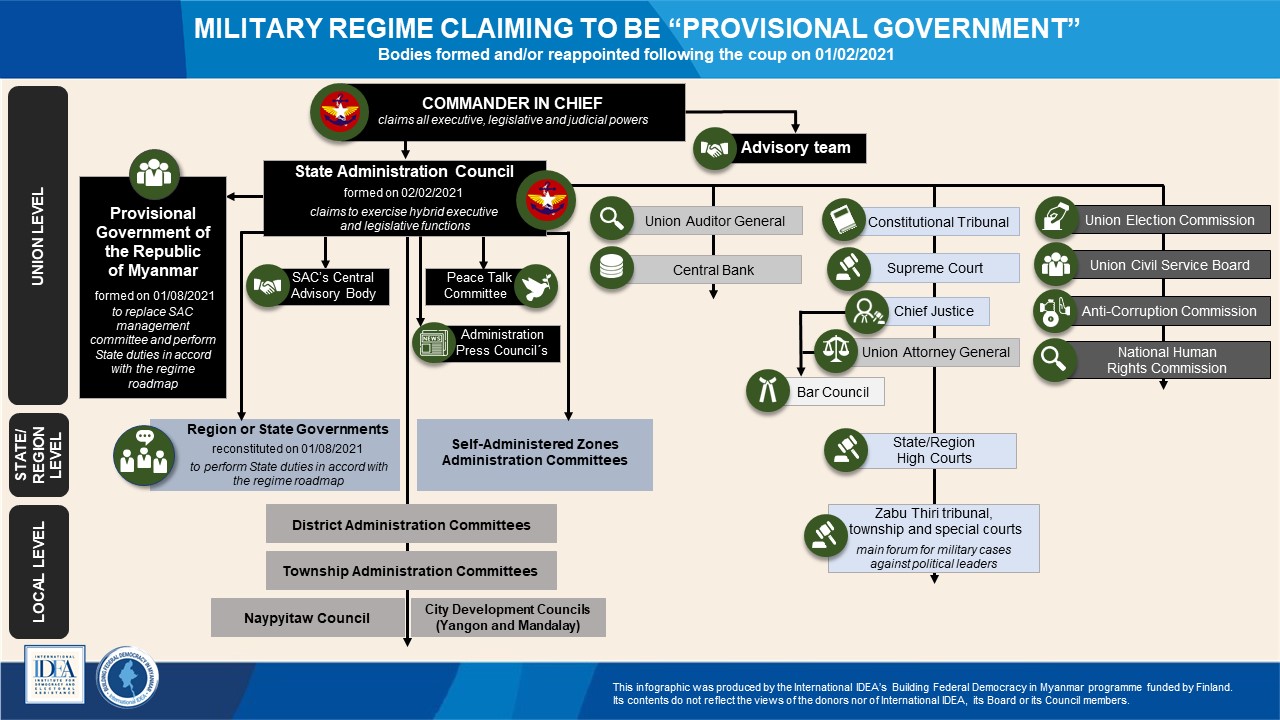

Since the coup, the military regime has attempted to consolidate power by using extreme violence, imprisoning civilian leaders, establishing new governing bodies and capturing existing institutions, while claiming to act in accordance with the 2008 Constitution. The Commander-in-Chief established a State Administration Council (SAC) consisting of 16 members – mainly military officials – purportedly tasked with assisting him in exercising legislative powers. The SAC established a ‘Provisional Government’ and appointed General Min Aung Hlaing as Prime Minister, a post that does not exist in the 2008 Constitution. Additionally, the military regime captured existing institutions, including the Constitutional Tribunal and the Election Commission, by appointing new members. General Min Aung Hlaing also extended the unconstitutional state of emergency until August 2023, 31 months after the coup took place.

Figure 1. Organizational chart of the military regime claiming to be the ’provisional government’ (click picture to zoom in).

The Federal Democracy Charter and Structure of the National Unity Government

The fact that the 2008 Constitution has been so severely violated and its authority undermined by the military’s unbounded actions has created a constitutional vacuum. Many stakeholders in the country believe that the social contract has been broken and consider the 2008 Constitution to be defunct and inapplicable since its terms have been so radically violated by the military’s illegal actions. The unconstitutional coup and the ensuing, escalating crisis have rendered the 2008 Constitution invalid and inapplicable.

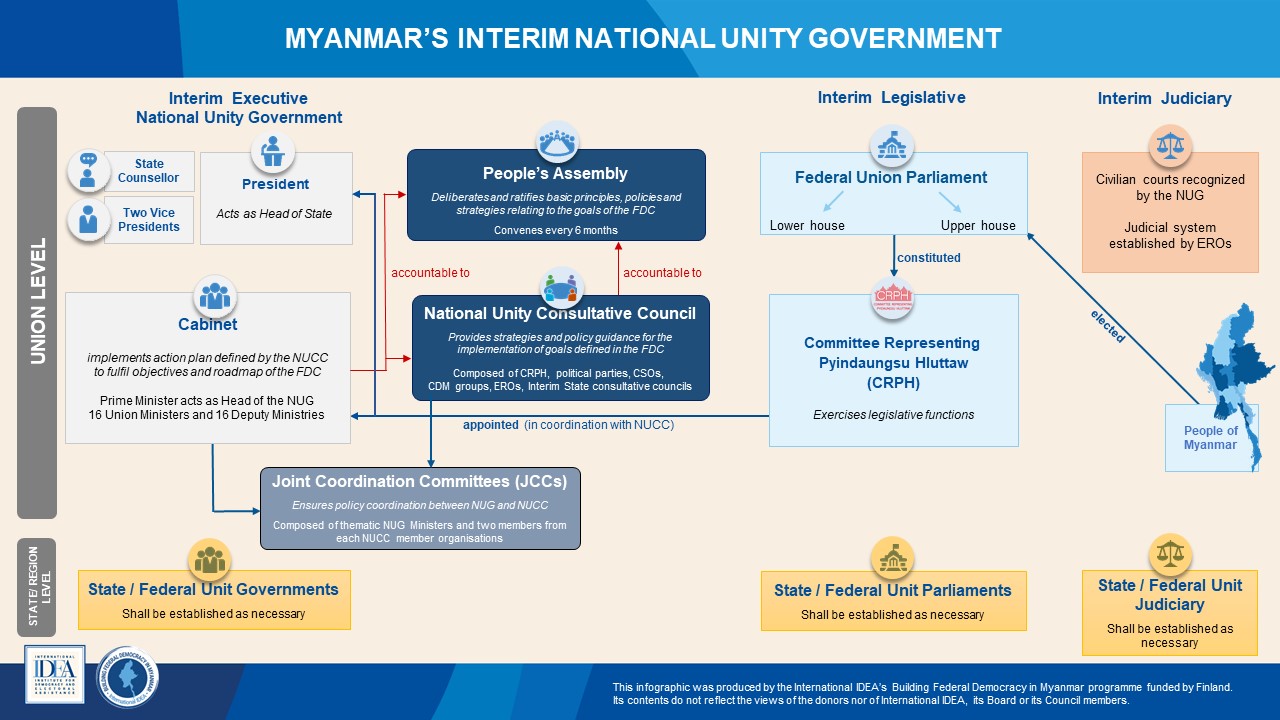

In response to the unconstitutional seizure of power by the military and the ensuing constitutional vacuum, a group of MPs who won seats in the 2020 general elections – and with the agreement of 80 per cent of all elected MPs – formed the Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH) to represent the democratically elected legitimate legislature. On 31 March 2021, the CRPH released the Federal Democracy Charter (FDC), which provides for the establishment of interim governing institutions and outlines a roadmap and core principles to defeat the military and transition towards a federal democratic union. Following months-long negotiations within the National Unity Consultative Council (NUCC), which brings together the CRPH with the other democratic stakeholder groups, the Charter was revised in January 2022. The Charter is a negotiated consensus document by the CRPH and other pro-democracy actors, such as civil society and strike committees, and ethnic group representatives thus specifying the terms of the political alliance against the military. The Charter establishes an interim governance arrangement (Part II) and a roadmap and core principles towards building a federal democratic union (Part I).

The interim governance system foreseen by the Charter includes the following institutions:

- An interim legislature named the Federal Union Parliament (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw) as a bicameral parliament, with two houses of equal powers. Both houses consist of parliamentarians elected in 2020 who do not cooperate with the military, and exclude military-appointed MPs. In practice, they have been convening online as one single, combined Union Assembly. Given the difficulty of convening the Union Parliament, the Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), which consists of 20 elected MPs, represents and acts on behalf of the Union parliament. The CRPH develops legislation based on strategies defined with the NUCC. The Union Parliament then formally adopts this legislation when it convenes.

- The National Unity Government (NUG) serves as the executive branch at the Union level in the interim period. The NUG consists of the President, two Vice-Presidents, the State Counsellor, the Prime Minister and cabinet ministers. The President and Vice-Presidents are heads of state, and the prime minister is the head of the cabinet. The NUG was appointed by the CRPH with the endorsement of the NUCC. The NUG is responsible to the NUCC and the People’s Assembly, but also reports to the CRPH and the Union Parliament.

- The People’s Assembly is an umbrella platform that consists of political forces opposed to the military regime and who have agreed to the goals and roadmap of the Federal Democracy Charter: a) elected members of parliament, including the CRPH, b) political parties, c) civil society organisations and strike committees, d) ethnic armed resistance organisations, and e) interim state consultative councils. The People’s Assembly convenes every six months and is responsible for deliberating and approving strategies for fulfilling the Charter’s goals.

- The National Unity Consultative Council (NUCC) acts as the People’s Assembly standing body. It consists of representatives from the five stakeholder groups who are also part of the People’s Assembly. The NUCC has been the platform at the forefront of conducting negotiations among political stakeholders. Its main role is to develop strategies and provide policy guidance to implement the Charter and fulfil the objectives defined therein. The NUCC also endorses legislation enacted and appointments made by the CRPH.

- Thematic Joint Coordination Committees consisting of relevant NUG ministers and delegates of each of the stakeholder groups represented in the NUCC. These committees aim to ensure communication and coordination between the NUCC and the NUG’s different ministries in defining and implementing, respectively, the strategies to fulfil the Charter's goals.

Figure 2. Organizational chart of the interim National Unity institutions (click picture to zoom in).

The Federal Democracy Charter contains a roadmap for the transition towards a federal democratic union. The Charter foresees three main periods – an interim period until the defeat of the coup by the NUG and the coalition of democratic forces, followed by a transitional period – to be governed by a (yet to be adopted) transitional constitution – during which a Constitutional Assembly will draft a new permanent federal democratic constitution which will be in place when the final period of the federal democratic union begins.

Besides laying out in broad terms the process for making a new constitution, the Charter also sets out substantive requirements that the new permanent constitution must meet. Notably, it foresees that the future constitution would establish a federal state structure where the constituent units would be granted a significant level of autonomy, and the security forces would be under civilian command and democratic oversight. The adherence to human rights and the rule of law, non-discrimination, gender equality, an inclusive concept of citizenship, as well as the principle of secularism are additional features enshrined in the Federal Democracy Charter that will further guide the process towards a new federal democratic constitution.

| Branch | Hierarchy | Appointment | Powers | Removal |

|---|

Share this article